The Empty Throne

Part 3 of The Sovereign Series: Why no one is driving, everyone assumes someone else has a plan, and three simple rules that could maintain optionality for the future.

Share this post:

Export:

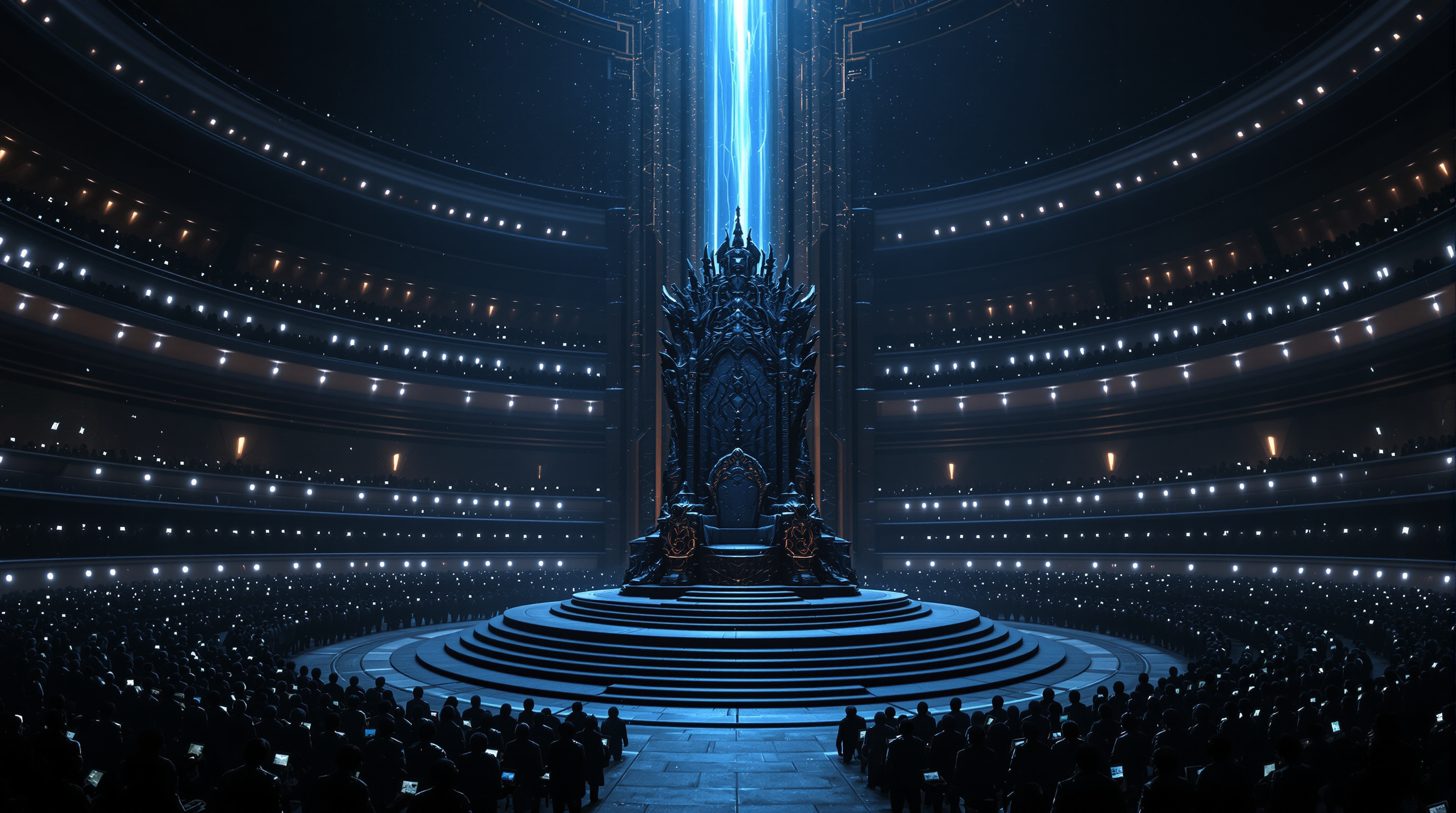

The Empty Throne

Part 3 of The Sovereign Series: Why No One Is Driving and What Simple Rules Could Maintain Optionality

Erik Bethke + Claude | January 1, 2026

Everyone who glimpses the structural problem of corporate concentration assumes someone smarter, more powerful, more positioned than them is already working on it.

The professor assumes the policy makers know. The policy makers assume the tech leaders have a plan. The tech leaders assume the market will sort it out. The market assumes the regulators are watching. The regulators assume the experts understand. The experts assume someone with power is listening.

The loop closes. No one is driving.

The Bystander Effect at Civilizational Scale

You know the psychology: when many people witness an emergency, each assumes someone else will act. Responsibility diffuses. No one calls 911. The victim bleeds out while bystanders wait for each other.

We're doing this at civilizational scale.

The terrifying corollary: The people most capable of seeing it are most likely to assume it's handled.

"I'm just an academic / investor / engineer / writer - if I can see this, certainly the people with actual power have already gamed it out."

But the people with actual power:

- Are inside the machine, optimizing locally

- Have quarterly earnings to hit

- Are selected for not seeing the big picture

- Assume the system is self-correcting because it always has been

The ability to see is inversely correlated with the power to act. And the power to act is inversely correlated with the ability to see.

Why the Silence?

If this is as significant as I've argued in Part 1 and Part 2, why isn't it being discussed?

1. The People Who Understand It Are Captured

Academic finance? Funded by asset managers. Publishes in a paradigm that assumes efficient markets. Challenging the paradigm means challenging your own funding.

Financial media? Owned by or dependent on the Magnificent Seven (directly or through advertising). Plus, "everything is fine, keep investing" is a better business model than "the system is eating itself."

Regulators? Revolving door with the industry. The SEC commissioners of tomorrow are the BlackRock executives of today. Who bites the hand that will feed them?

Politicians? Tech donations. Lobbying. And genuine inability to understand the mechanics. Try explaining market cap weighting to your senator.

2. The Language Doesn't Exist Yet

We're using 20th century concepts for a 21st century phenomenon:

-

"Monopoly" - But they don't fit the Standard Oil model. They're not cornering a commodity. They're infrastructural to the economy itself.

-

"Market concentration" - But it's not a traditional antitrust problem. The concentration is caused by the structure of investing itself, not predatory behavior.

-

"Bubble" - But it's not irrational exuberance. It's structural. The money flows in regardless of valuation because 401ks are automated.

-

"Too big to fail" - Getting closer. But "too big to fail" implied temporary support during crisis. This is "too big to exist outside of" - a permanent condition.

We literally don't have vocabulary for: "A self-reinforcing index-sovereign that prints equity-currency while extracting rents from infrastructure it made mandatory."

Without language, thoughts can't stabilize. They slip away. You glimpse it, but you can't hold it. The concept slides out of focus.

3. Everyone Is Inside the System

- Your 401k? Passive index funds.

- Your pension? Same.

- Your savings? Probably at a bank that holds these stocks.

- Your job? Likely depends on one of their platforms.

Criticizing this is criticizing the thing everyone's retirement depends on.

It's like fish describing water - except the fish's survival depends on not noticing. Not because someone forbids noticing. But because noticing is existentially uncomfortable.

If the system is broken, what do you do with your 401k tomorrow morning? There's nowhere else to put it. There's no outside.

4. It's Working (For Now)

The strongest argument against taking this seriously: stonks go up.

Until there's a crisis, it's "not a problem." And anyone who points at the structure gets dismissed as a permabear, a crank, or someone who missed the rally.

This is the deepest capture of all. Success silences criticism. The longer it works, the more insane it seems to question it. Until suddenly it doesn't work, and everyone says "why didn't anyone see this coming?"

They did see it coming. But seeing it coming sounds crazy until it comes.

The Practical Definition of Crazy

Here's where I have to be honest about my own position.

Sane: Shares the consensus model of reality. Functions within accepted parameters. Assumes the system is coherent.

Crazy: Sees something the consensus doesn't. Can't unsee it. Acts or speaks in ways that don't fit the shared frame.

By this definition, writing these essays is crazy.

But here's the thing: the consensus is also crazy. It's just distributed crazy, so it doesn't pattern-match as insanity:

- Believing "someone is in charge" - not true

- Believing the market is efficient - not true in any meaningful sense

- Believing passive investing is diversification - increasingly fictional

- Believing democratic governance controls corporate sovereignty - inverted

- Believing your retirement is "safe" in index funds - you own a leveraged bet on 7 companies

The consensus is a shared hallucination that's functional until it isn't.

Some of us have just stopped sharing it.

Three Simple Rules

What would maintaining optionality look like? Not fixing everything. Just keeping the light cone open - preserving the possibility of different futures rather than locking in the current trajectory.

Here are three simple rules that could do it:

Rule 1: No Buybacks Unless You Buy the Whole Float

Current state: Public companies manipulate their own stock price through buybacks. They get the liquidity benefits of public markets and the supply control of private ownership.

The rule: If you want to buy back shares, you must tender for 100%. Either be public (accept price discovery) or be private (control your equity). Not both.

What this does:

- Ends the reflexive loop where buybacks lead to higher price which leads to higher index weight which leads to more passive buying

- Forces a binary choice: accept the full weight of public price discovery, or go private

- Removes the central bank-like control companies currently have over their own equity

Rule 2: Automatic Sherman Breakup at $100B Market Cap

Current state: There's no upper bound on corporate scale. Network effects compound without limit. The biggest get bigger because they're big.

The rule: When a company's market cap crosses $100B, automatic antitrust proceedings begin. Not as punishment, but as mitosis. You succeeded; now you split.

What this does:

- Hard ceiling on sovereignty accumulation

- Maintains the possibility of competition and alternatives

- Prevents "too big to regulate, too big to comprehend" scale

- $100B is still enormous - a massive, successful company. You just don't get to become a civilization-layer monopoly.

The number could be debated. The principle is: past a certain scale, you're no longer a market participant. You're a market structure. Structures need different governance.

Rule 3: Public Companies Taxed at Half the Private Rate

Current state: Smart money stays private as long as possible. Extract value, grow in the dark, then dump onto public markets. Public markets - supposedly a public good for price discovery and democratic ownership - are treated as exit liquidity for private capital.

The rule: Public companies pay half the corporate tax rate of private companies.

What this does:

- Reverses the incentive to stay private and opaque

- Rewards transparency and public accountability

- Makes going public attractive again

- Treats public markets as the public good they're supposed to be

Why These Rules Won't Pass

Let me be clear: these rules will not be implemented. Not because they're bad ideas. Because the people who would need to pass them:

- Own index funds

- Receive donations from the Magnificent Seven

- Use their infrastructure daily

- Literally cannot imagine the alternative

And the asset managers (BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street):

- Their entire business model depends on passive concentration

- They vote the shares

- They employ the regulators' future selves

The system is load-bearing now. Everyone's retirement is stacked on top of it. Changing the rules feels like pulling a Jenga block from the bottom.

And yet - the rules are simple. A paragraph each. The complexity isn't technical. It's political and psychological.

We can't imagine changing it because we can't imagine what we'd be without it.

The Bootstrapping Problem

To implement human-scale systems, you need:

- Legislative action - but it's captured by the entities you're regulating

- Regulatory enforcement - but it runs on their infrastructure

- Popular movement - but it's mediated through their attention platforms

- International coordination - but they're already transnational, states aren't

There's no Archimedean point outside the system.

The only entities with enough power to enforce new rules are... the entities the rules would constrain.

This is the Cincinnatus problem. Washington walking away. The dictator who abolishes the dictatorship. It almost never happens. But when it does, it's civilization-defining.

What Can Actually Be Done?

I don't have a satisfying answer. If I did, I'd be doing it rather than writing about it. But here's what I've got:

See Clearly

The first step is seeing. Not looking away. Not assuming someone else is handling it. Just... seeing what has happened and naming it plainly.

These essays are an attempt at that. Maybe they help someone else see. Maybe they give language to something that was previously unspeakable. Maybe they're just a record that someone noticed.

Reduce Personal Dependence

To the extent possible, reduce your exposure:

- Diversify outside passive index funds (if you can find alternatives)

- Build skills that don't depend entirely on platform access

- Create relationships outside their social graphs

- Question defaults (why is your 401k in target-date funds?)

This won't change the system. But it might change your resilience within it.

Find the Others

The bystander effect is broken when people coordinate. When you see someone else acting, the diffusion of responsibility ends.

If you read this and it resonates, you're not alone. There are others who've peeked around the corner. Finding them matters. Even if "action" is just conversation - just seeing together - that's something.

Maintain the Conversation

The silence is load-bearing for the system. Every conversation that breaks the silence is a small crack in the edifice.

I'm not naive about this. Talk is cheap. Essays don't change power structures. But articulation is the precondition for action. You can't coordinate around something you can't name.

The Empty Throne

There is no council of elders secretly managing this. There is no deep state with a plan. There is no Illuminati steering toward a goal. There are no adults in the room.

The throne is empty. It's been empty the whole time.

What sits there instead is a system - a set of interlocking incentives and feedback loops that no one designed and no one controls. It optimizes for its own continuation. It rewards those who serve it and marginalizes those who question it. It looks like governance, feels like governance, but is actually just... momentum.

This is either terrifying or liberating, depending on how you look at it.

Terrifying because: no one is coming to fix it. The cavalry isn't arriving. There's no appeal to higher authority because there is no higher authority.

Liberating because: the system that feels omnipotent is actually emergent, contingent, and - in principle - changeable. It wasn't designed, so it could be redesigned. The rules that created it could be replaced with different rules.

The question is whether enough people can see clearly at the same time, for long enough, to coordinate action.

History suggests: probably not, until crisis forces the issue.

But history is written by survivors. And sometimes the crazy ones who saw early turn out to be the ones who kept the light cone open.

Conclusion

On January 1, 2026, let me offer this:

The Magnificent Seven have become corporate sovereigns through structural mechanisms no one designed. (Part 1)

Passive investing created a strange attractor that concentrates power, destroys price discovery, and has no natural exit. (Part 2)

The silence around this is itself a symptom of the capture - everyone assumes someone else is handling it. (This essay)

Three simple rules could maintain optionality: No buybacks without buying the float. Automatic breakup at $100B. Tax advantage for public companies. But the rules won't pass because the system is load-bearing.

The throne is empty. No one is driving. The system optimizes itself.

What you do with this seeing is up to you. I can't tell you there's a plan that works. I can only say: you're not crazy for noticing. The consensus that everything is fine is the crazier position. It's just distributed crazy, so it passes for normal.

Maybe nothing changes. Maybe the loop continues until some external shock resets the board. Maybe the light cone closes and this becomes the permanent architecture of human economic life.

Or maybe - just maybe - enough people seeing clearly at the same time creates the conditions for something better.

I don't know. But I'd rather see and be wrong than not see at all.

This is Part 3 of The Sovereign Series. Part 1: The New Sovereigns establishes the frame. Part 2: The Strange Attractor examines the mechanism. For those who want to go deeper, Part 4: Memetic Life Forms explores what corporations actually are.

Related Posts

Memetic Life Forms

Part 4 of The Sovereign Series: What if corporations aren't tools we built, but living entities that evolved to farm us? What if ownership is a story ...

The Strange Attractor

Part 2 of The Sovereign Series: How passive investing grew from 3% in 2000 to over 50% today, creating a self-reinforcing loop that concentrates power...

The New Sovereigns

Part 1 of The Sovereign Series: Seven companies now exercise more effective sovereignty than most nation-states. They print currency, tax commerce, ma...

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Get notified when I publish new blog posts about game development, AI, entrepreneurship, and technology. No spam, unsubscribe anytime.

Comments

Loading comments...

Published: January 2, 2026 4:44 AM

Last updated: February 10, 2026 4:38 AM

Post ID: b2665453-2eee-4bb6-8679-29782891d1d6